Shakers and Animal Husbandry

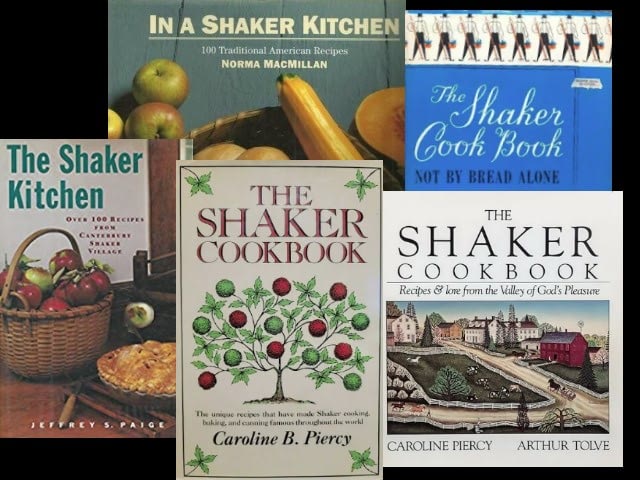

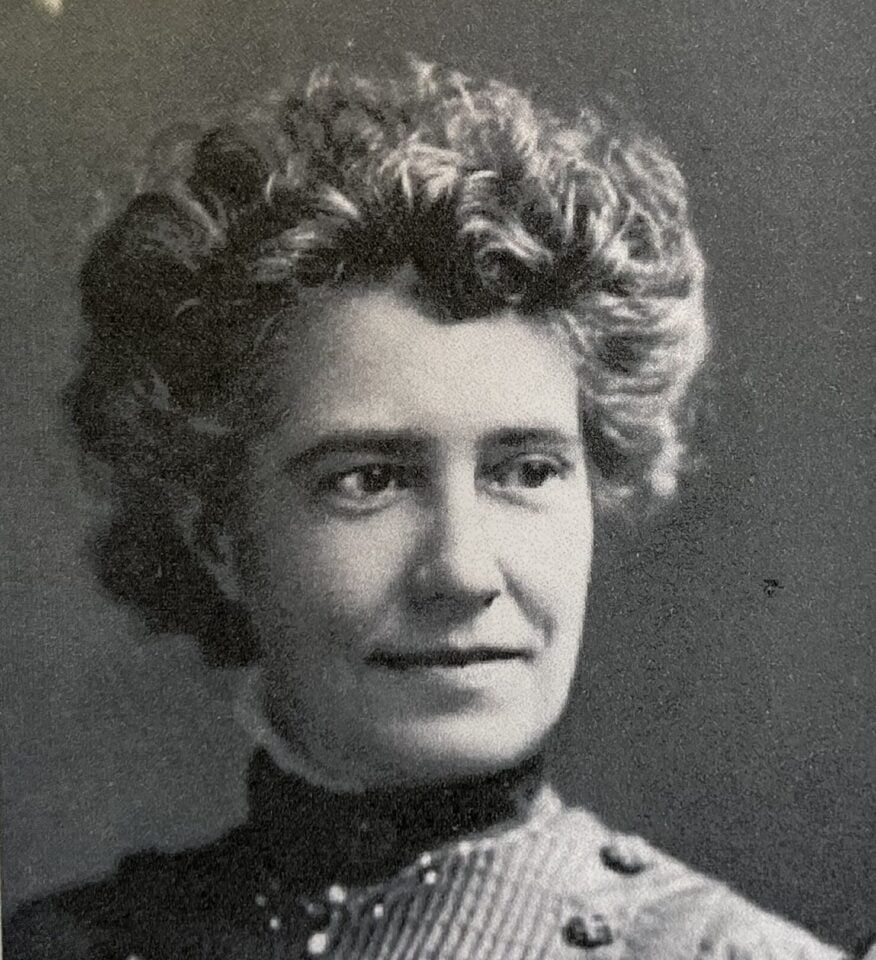

As she writes in her book, “Growing Up Shaker,” when Frances A. Carr and her little sister were left at a Shaker community by their desperate mother, the then Catholic Frances’ first major religious dilemma was in the form of a meat dinner on a Friday. While the meal was probably meant to be a special treat for the girl, perhaps to ease her into her new life, the young Frances would ultimately reject the meal, which the other children ate eagerly. The story provides evidence of the livestock farming that the Shakers participated in. While Shakers were often thought of for their vegetarianism, many Shaker communities did eat meat. The Shakers grew livestock for a variety of reasons: to have animal products, like dairy or wool, to sell at market and to produce meat both for their own communities and to sell for a profit. Shakers grew a variety of livestock, including chickens and sheep, but cattle and, for a period, swine were of particular importance.

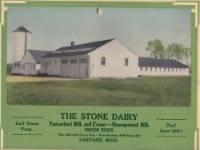

Selling dairy products was a key part of many Shaker communities’ income.

Perhaps the most important of all livestock animals in Shaker communities were cattle. Cattle were raised for the community’s consumption of their meat and dairy and also to sell in the marketplace. Selling dairy products, in particular, was a key part of many Shaker communities’ income and thus their ability to be self-reliant. Opposed to mass farming of cattle, Shakers were careful and diligent farmers of smaller herds of much higher quality cows. Varieties of cattle one might find in Shaker communities would be the classic black and white dairy cows, Holsteins and shorthorns, for meat. Frances A. Carr would later write of the tradition in her Shaker community to eat cheese by itself as a meal.

While the Shakers constantly kept cattle as livestock,

the Shakers had a more complex relationship with pigs.

Chickens have eggs, cows have their milk, sheep have their wool, but pigs have only their meat. In terms of subsistence farming, pigs are probably one of the more unfortunate of livestock animals, yet they were essential to early New England colonial life, including the Shakers. Until the 1840s, the Shaker communities widely farmed, bred, sold, and ate swine, according to Murray & Coşgel in “Market, Religion, and Culture.” Similar to their cattle breeding, Shakers were known for their high quality and well-bred swine. In Ohio, the Shaker community of Union Village bred a precursor to the modern-day Poland China hog by breeding Bedford pigs with feral hogs and then with the common Berkshire pigs. Despite swine’s economic importance to Shaker communities, a religious revelation occurred in 1841 in the New Lebanon community that declared that pork should be banned from both farming and eating as it was “cursed and unclean.” (Murray & Coşgel, 567) The idea of pork being unclean has cultural roots as far back as the Old Testament, with God declaring to Moses, “And the pig, though it has a divided hoof, does not chew the cud; it is unclean for you. Of their flesh shall ye not eat, and their carcase shall ye not touch; they are unclean to you.” (King James Bible, Leviticus 11: 7-8). The ban was slow moving and never fully succeeded in completely eradicating some Shaker communities’ farming of pigs.

Industrialization of farming in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Shakers experienced the shift from subsistence-based farming, which is based not on profit but rather survival, present in the earlier colonial period, to the rapid industrialization of farming of animals in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the late 19th century, a great deal of criticism was put on the meat industry for its unsanitary and inhumane conditions, exposed by Upton Sinclair’s novel “The Jungle.” Much of the same criticism is still aimed at the modern meat and animal-farming industry. In many communities, there is a move to support local animal farmers over big corporations. This “green eating movement” can be seen in the popularization of farmers markets and emphasis on less but higher quality and ethically raised meat. While these attitudes towards animal farming and food in general can feel like modern concepts, Shakers’ rich history of animal husbandry reflects similar ideals of the modern-day “green food” movement.

Citations:

Bowen, Joanne. “To Market, to Market: Animal Husbandry in New England.” Historical Archaeology, vol. 32, no. 3, 1998, pp. 137–52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616636.

Carr, Frances A. "Growing Up Shaker." The United Society of Shakers, 1994.

Murray, John E., and Metin M. Coşgel. “Between God and Market: Influences of Economy and Spirit on Shaker Communal Dairying, 1830-1875.” Social Science History, vol. 23, no. 1, 1999, pp. 41–65. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1171540. Accessed 30 June 2025.

Murray, John E., and Metin M. Coşgel. “Market, Religion, and Culture in Shaker Swine Production, 1788-1880.” Agricultural History, vol. 72, no. 3, 1998, pp. 552–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3744570.