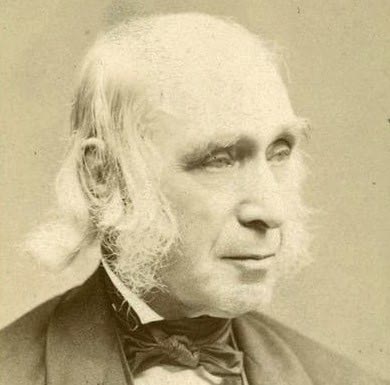

Amos Bronson Alcott

November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888Amos Bronson Alcott was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style and avoiding traditional punishment. He hoped to perfect the human spirit and, to that end, advocated a plant-based diet. He was also an abolitionist and an advocate for women’s rights.

Born in Wolcott, Connecticut, in 1799, Alcott had only minimal formal schooling before attempting a career as a traveling salesman. Worried that the itinerant life might have a negative impact on his soul, he turned to teaching. His innovative methods, however, were controversial, and he rarely stayed in one place very long. His most well-known teaching position was at the Temple School in Boston. His experience there was turned into two books: “Records of a School” and “Conversations with Children on the Gospels.” Alcott became friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson and became a major figure in transcendentalism. His writings on behalf of that movement, however, are heavily criticized for being somewhat incoherent. Based on his ideas for human perfection, Alcott founded Fruitlands, a transcendentalist experiment in communal living. The project was abandoned after seven months. Alcott and his family struggled financially for most of his life. Nevertheless, he continued focusing on educational projects and opened a new school in 1879, even though he was near the end of his life. He died in 1888.

Alcott married Abby May in 1830, and they had four children, all daughters. Their second was Louisa May, who fictionalized her experience with the family in her novel “Little Women” in 1868.

Fruitlands Transcendental Community

Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane founded “Fruitlands” in 1843. Lane and Alcott collaborated on a major expansion of their educational theories into a Utopian society. Alcott, however, was still in debt and could not purchase the land needed for their planned community. In a letter, Lane wrote, “I do not see anyone to act the money part but myself.” In May 1843, he purchased a 90-acre (36 hectare) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts. Up front, he paid $1,500 of the total $1,800 value of the property; the rest was meant to be paid by the Alcotts over a two-year period. They moved to the farm on June 1 and optimistically named it “Fruitlands” despite only ten old apple trees on the property. In July, Alcott announced their plans in The Dial: “We have made an arrangement with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres, which liberates this tract from human ownership”.

Their goal was to regain Eden, to find the formula for agriculture, diet, and reproduction that would provide the perfect way for the individual to live “in harmony with nature, the animal world, his fellows, himself, [and] his creator.” In order to achieve this, they removed themselves from the economy as much as possible and lived independently, styling themselves a “consociate family.” Unlike a similar project named Brook Farm, the participants at Fruitlands avoided interaction with other local communities. At first, scorning animal labor as exploitative, they found human spadework insufficient to their needs and eventually allowed some cattle to be “enslaved.” They banned coffee, tea, alcoholic drinks, milk, and warm bathwater. As Alcott had published earlier, “Our wine is water, — flesh, bread; — drugs, fruits.” One member, Samuel Bower “gave the community the reputation of refusing to eat potatoes because instead of aspiring toward the sky they grew downward in the earth.” For clothing, they prohibited leather, because animals were killed for it, as well as cotton, silk, and wool, because they were products of slave labor. Alcott had high expectations, but he was often away attempting to recruit more members when the community most needed him.

The experimental community was never successful, partly because most of the land was not arable. Alcott lamented, “None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed so we fell apart.” Its founders were often away as well; in the middle of harvesting, they left for a lecture tour through Providence, Rhode Island, New York City, and New Haven, Connecticut. In its seven months, only thirteen people joined, included the Alcotts and Lanes. Other than Abby May and her daughters, only one other woman joined, Ann Page. One rumor is that Page was asked to leave after eating a fish tail with a neighbor. Lane believed Alcott had misled him into thinking enough people would join the enterprise, and he developed a strong dislike for the nuclear family. He quit the project and moved to a nearby Shaker family with his son. After Lane’s departure, Alcott fell into a depression and could not speak or eat for three days. Abby May thought Lane purposely sabotaged her family. She wrote to her brother, “All Mr. Lane’s efforts have been to disunite us. But Mr. Alcott’s … paternal instincts were too strong for him.” When the final payment on the farm was owed, Samuel May refused to cover his brother-in-law’s debts, as he often did, possibly at Abby May’s suggestion. The experiment failed and the Alcotts had to leave Fruitlands.

As winter approached, some members of the Alcott family grew increasingly unhappy with their Fruitlands experience. At one point, Abby May threatened that she and their daughters would move elsewhere, leaving Bronson behind. Louisa May Alcott, who was ten years old at the time, later wrote of the experience in “Transcendental Wild Oats” (1873): “The band of brothers began by spading garden and field; but a few days of it lessened their ardor amazingly.”

Partially sourced from Wikipedia. See full Wikipedia article