Five Churches, One Site

The following is a history prepared for the Harvard Branch Alliance and delivered on Thursday,

November 9, 1967 at the Helen Stone Bigelow Room by Miss Elvira Scorgie.

I have been frustrated for some years by requests for a history of the church but “please make it not more than 3 inches long,” – 225 years at hardly less than 100 years to the inch. So I have been generously granted permission to speak today on the low lights of church history, the high lights having already been dinned into you. I am confining myself with as few digressions as my self control will admit to the meeting house and its structure, bearing in mind an incident that happened to me last summer when I was guiding at Fruitlands.

The woman guest seemed unusually interested; she kept peering at me apparently fascinated. I was naturally flattered. But when I had finished all I could think of to say, and paused for breath before passing on to the next object, she piped up, “Have you all your own teeth?”

It may be some years since you have read “Alice in Wonderland” but surely you remember the oft quoted remark of the King of Hearts to the White Rabbit in the final chapter. “Begin at the beginning and go on until you come to the end – then stop.” This is generally quoted as an admonition to those speakers who are so enamored of their own voices that they go on speaking after they have said all they have to say. I hope I will have the sense to stop when I get to the end, but my problem is to begin at the beginning. What is the beginning of our church?

In the petition for autonomy, the petitioning inhabitants of the three towns involved, state that for several years they have been accustomed to meet at a house for public worship, which in a later document they stated had been built by themselves. The location is inadequately described, but by tradition was on the present Ayer Road at the junction of that road with Harvard Depot Road, or near the extreme northern limits of Lancaster about one mile from the border of Stow. This congregation was not formally organized; they left no known records as to when it was started nor whom they employed as minister. As they were never held to account for non-church attendance in the three towns, they probably engaged licensed ministers and perhaps also paid double tithes to the various towns and also to their own minister. If the towns got money, they weren’t overly particular about non-attendance. But as they were not Harvard residents and the house they occupied was not yet on Harvard ground, this meeting place may be considered merely as a prelude to the building of the first meeting house.

Let us begin, therefore, with the first meeting house erected by the Town of Harvard. I was somewhat distressed to find that Mr. Goodnow was to speak on meetinghouses at the last meeting as I feared that what I have to say would be an anticlimax, but on consideration, I find that my talk will supplement his lecture, showing how Harvard coincided or differed as the case may be, with what was done in other communities.

We have, of course, no picture of the first meeting house, but it was undoubtedly on conventional lines. It was 48 ft. in length, 35 ft. wide and 20 ft. between the joists. That is actually larger than our present auditorium – our ancestors would be horrified at calling it a sanctuary. You can’t have noisy town meetings in a sanctuary – and they were hilarious in the early days and still consider it sanct. There was 144 sq. ft. of crown glass, perhaps two tiers of four windows each on each side, and the pulpit window in the rear. There may have been a small window in front also but this is dubious. I cannot figure out the exact proportions, crown glass according to the dictionary is round. There was no porch, therefore the gallery stairs were outside. Galleries round three sides, of course, three rows deep, and sixteen box pews on the floor and the rest open benches. A later town record, February 16, 1745, states “it was voted that the town stock be kept in the meeting house. Lest anyone should think that this refers to the instrument of punishment, let me add that the record was later amended by the Town Clerk to read that the town stock of ammunition be kept in the loft of the meetinghouse. So there was also a loft. This last is a little ahead of my story, but I wanted to lug in the loft.

Having voted to build to these specifications, the next thing was to select a site, and this caused a hassle. It is really too bad that all the arguments on this article are nowhere recorded, because the fact was that the final decision was to build on a piece of common land about where the Town Hall now stands. Whether it was pointed out to the voters at the time, or whether they found out soon afterward, does not appear in the records, but the fact is that the land did not belong to Harvard at all; it was owned by Lancaster. So the town voted to petition for this tract of land for a meeting house, training field, burying ground, and what have you. This land must have had some known abbuters but none are mentioned in the petition. It could not be called Lancaster common land; Lancaster Common was where the Girls’ Industrial School is located, so it was christened hopefully Meeting House Plain, in honor of the projected meeting house. I wish we had kept the name.

Lancaster obliged. They had little use for a small piece of rocky land entirely surrounded by Harvard. They went further, in fact, and when a minister was finally settled in Harvard, they presented him with two islands in Bare Hill Pond, probably all the islands there were before the dam was built. Ministers Island certainly was part of the mainland. I have seen an old plan showing it so.

Lancaster retained title to the roads, however, until 1791, and as it was the custom for taxpayers to work out their taxes with road work, it must have caused much confusion. But here I am diverging again.

The walls and roof of the meeting house were built of pitch pine, not today considered a desirable wood. I exclaimed at this to the Town Clerk, who was also a carpenter, who was showing me the records, but he said that hard pine, as it is also called, is extensively used for similar purposes. The boards were not local – why I can’t imagine. Harvard has never been short of lumber, but John Daby, our local miller, made a journey to Groton to procure them. There were also 363 ft. of rails and 735 ft. of planks for the seats.

One big expense was digging rocks. John Daby put in 3 days work. It was not beyond the dignity of the chairman of the Board of Selectmen to do likewise and in addition, one day for his oxen. Probably, most of the able-bodied men of the town did likewise.

Another big expense was nails which had to be made laboriously by hand. We have a most peculiar vote on March 16, 1733 to pass over the motion to buy nails. Perhaps they thought they could get a lower bid or did they think wooden pegs would suffice? On second thoughts it was voted on August 30, to provide 30 pounds to buy nails. As all the wood used came to only about eleven pounds, this seems out of proportion for the nails, but it is possible that other wood was donated which doesn’t appear in the town records.

The frame was raised June 20, 1733 and the building committee was instructed to finish the building as quickly as possible, to wainscote the interior 4 or 5 ft. from the floor, lath and plaster the sides and roof, and glaze the windows and build the pulpit. The pews were to be built by the owners, thereof.

Than came the great day of the ordination of a settled minister and the organization of the church. Harvard strutted her stuff. Ministers and lay delegates and friends came from near and far. Joseph Willard dined 38 ministers and delegates and 38 horses. Mr. Secomb, the newly elected minister, appeared with 9 relatives on 9 horses and stayed with Joseph Willard for two nights, 18 shillings a piece for the horses, 6 shillings for the men. It was more profitable to be a horse than a minister in those days.

There have been some changes since Joseph Willard’s days. He lived then at the Junction of Groton Road and the Road to Brook Meadow. Groton Road has since been renamed Prospect Hill Road. The Road to Brook Meadow became immediately and inevitably the Road to the Meeting House… later with the building of other meeting houses, the Road to Harvard Center and now-a-days that portion of Still River Road from the corner of Prospect Hill to Under Pin Hill Road… showing the shift in the focus of interest.

Some structural defect occurred, probably a leaky roof, which occasioned the adjournment of the Town Meeting of August 26, 1734 to the old meeting house; the last time the town met in that building and the only time it was dignified by the name of Meeting House.

By July, 1737, the town was still in arrears for paying for the meeting house but managed to pay John Wright for boarding the plasterers; whether the plastering or the bill was delayed is a moot question. There is no bill for the plastering itself – obviously, local talent. Of course, you must understand that at an age when money was so very scarce, it was more economical to give a days’ work than to be assessed to pay someone else to do do it.

The same year a canopy was put over the door at a cost of 1 pound, 10 sh.

In 1749, liberty was given to eight young men to build an additional pew over part of the stairwell on the men’s side, there being two straight flights of stairs, and at the same time a growth in population is indicated by a vote to add an extra row of seats round the galleries; whether by enlarging the same or by squeezing the already existing seats does not appear.

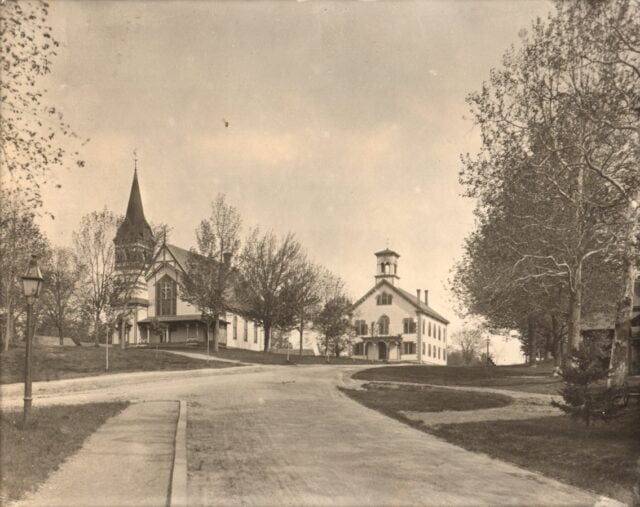

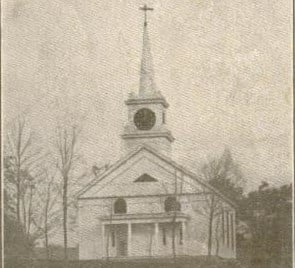

Unitarian Church 1840-1875

There has been no mention of paint. It may have been taken for granted, but often early buildings were not painted. However, this may be, it is not surprising in either case that after 24 years the meeting house was in need of repairs, not specified, and it was so voted. Also to finish stoning the same. What does this mean? Did they build the meeting house first and put in the foundations later? As the building committee had been discharged it was up to the Selectmen.

In 1762, it was voted to purchase a covering for the “cushing. “This, I take it, was for the Bible to rest upon, not the minister. In fact did the minister ever get a chance to sit down? He could not lurk behind the pulpit as our minister does while the choir is singing; there was no choir to sing. The collection was taken up on a weekday by the assessors at the same time they collected the real estate tax.

All these additions being insufficient for the growing needs of the town, an article was placed in the annual warrant March 5, 1770, to build a meeting house. It did not pass. On March 2, 1772, the question came up again and again it was defeated, but on August 24 of the same year it was finally voted to build. End of Chapter One.

The second church was to be 65 ft. long, 45 ft. wide and 27 ft. post. It was wisely decided to leave the old building standing until the new one was finished. As it was still to be the town house, they had all the Common to choose from.

An innovation was that the newly formed building committee was instructed to draw out a plan more particular by viewing some meeting house or consulting some experienced workman. The amateur construction of the first meeting house seems to have had some problems. A plan was brought in September 7, 1772, and was accepted. Too bad we don’t have that plan now. The town was by a remarkable feat of mathematics divided into five quarters for work and lumber. There were to be three porches, one on each side and one in front, none of course, behind the pulpit.

Two weeks later, (town meetings were the great mode of entertainment) voted to underpin the meeting house and porches 1-1/2 ft. deep under the sills, faced an pointed with lime. Likewise, the sills bedded in lime, the wall a proper thickness for strength and convenience of finishing, not less than 1-1/2 ft. thick, the outside to be white pine boards.

Another innovation was to let out the building to one man, whoever would do it cheapest, except for the frame. Oliver Atherton offered to do it for 790 pounds and to receive the stuff which Mr. Scolley had provided for said house at the price it cost as part of said sum. Voted that Mr. Atherton have it. Nothing more is said about the parishioners supplying work and lumber.

Having got so far they now had to decide on a location. Another hassle, but finally ironed out – a little south of the first meeting house. Our three succeeding churches have been built on the same site.

On July 14, 1773, the town accepted the frame which Oliver Atherton (he wasn’t supposed to build the frame but he did) had built and the great day for raising the same was appointed, requiring 160 men, one barrel of West India rum, one barrel of New England rum, 100 lbs. brown sugar, 8 barrels of cider, 8 barrels of beer and dinners of meats fresh and salt, roast and boiled – very like one of our district conferences today, except no rum.

It was voted to have banisters to the pews. Voted the pews to be 3 ft. 10 in. in height from the pew floor, wall pews to the 5-1/2 ft. wide from the wall all round on the lower floor. But on Dec. 20, 1773, voted not to reconsider the vote on banisters but that the vote on height of pews be null and void. I find no other vote on this subject. What height were they finally? You have the banisters floating in air without the pews.

May 16, 1774, voted to level the ground and place steps toward the east a gradual descent 12 ft. from the end of the porch, then an upright wall supposed to be high enough for a horseblock the most of the way till it come 10 ft. south of the south porch then to level a gradual descent from the house and porch to the natural ground all around the meeting house opposite to the east door in said upright wall likewise steps toward the south at the end of said wall. Voted to have stone steps.

Although Mr. Oliver Atherton was given the entire job of building, he must have let out some portions to others as on Oct. 24, 1774; Voted to accept the inside work of said meeting house; Voted to accept the roof upon Mr. Willard’s proposal to make the roof good, wherein he was deficient in shingling or in laying on bad shingles within a year from this time. I am surprised that the deacon tried to short change the town. Voted to accept the outside doors upon Mr. Richard Harris, Jr. mending said doors to the satisfaction of Phinehas Fairbank chosen by the town for that purpose. Voted to accept the roof of the south porch provided Mr. Oliver Atherton do the best of his endeavor with what lead there is now on it. These amateur carpenters!

Chose a committee to view the clapboarding. The committee reported October 26: It is our opinion that Mr. Oliver Atherton fill the cracks in the clapboarding with putty or paint of the same color in which they are now laid and that he secure the roof of the south porch from leaking. That south porch again. They said Mr. Atherton was engaged to do this.

Mr. Harris also mended the outside door to the satisfaction of Phinehas Fairbank and they were accepted. It is to be hoped that the deacon also mended his ways and his bad shingles, but that is not mentioned.

There was no ceremony connected with the occupation of the new meetinghouse. In fact, the exact date is not recorded and uncertain. About this time the Baptist Society was organized, but the two societies seem to have managed to exist in harmony. The ministerial tax collected by the assessors from the Baptists was turned over to them for the support of their own church and as for repairs to the meetinghouse, it was still the town hall and enjoyed by all residents of any denomination. The Baptists may have objected though there is no record of it, but many of them, perhaps the majority, were residents of other towns, and so they were greatly outnumbered at town meeting.

The project of a steeple first came up in 1794 but it was voted not to build. The question came up again in 1806 when it was voted to build a tower and steeple at the east end of the meeting house. Mr. Phinehas Sawyer will build the tower and steeple and find all the materials for the same from the bottom of the sells to the top of vane, to finish it suitable for such a building and to paint the same as the meetinghouse is or may be painted before the completion of said tower, etc., which is to be done by the first day of December next, and on condition that the town pay the said Phinehas Sawyer $200 on the first day of September next and $200 on the first day of each four following months making in the whole $1000 provided the town be at the expense of said tower and steeple and the said Phinehas to have the porch now standing at the east end of the meeting house and he the said Phinehas is to make good all repairs where any breach is made in the meeting house in putting up said tower, etc.

This was in July, but in December it was further voted not to exempt persons of other denominations from paying for the tower, etc. which was to be used for more than call to Sunday worship but the Shakers had no use for it. They were a community by themselves. It was very generous for the town to take that into consideration, and in March vote to exempt them. Of course, the Baptists and Methodists demanded and acquired exemption also.

Though this bell and tower were paid for solely by the Congregationalists, the town proceeded to lay down rules for the ringing. September 24, 1807, voted that the Bell should be rung on Sundays one hour before morning service begins, ten minutes, and five minutes at the time the service begins. When the minister appears in sight to toll the bell until he gets into the pulpit and likewise half an hour before the afternoon exercise begins to be rung ten minutes, and five minutes at the time it begins and to be tolled as above, and on week days to be rung at twelve o’clock and nine o’clock ten minutes each time. At funerals the bell to be tolled at nine o’clock in the morning of the day any person is to be buried ten minutes, and at the time of the funeral is appointed ten minutes, and begins to toll when the procession appears in sight and continues until it comes out of the grave yard and also to be rung at all lectures and town meetings until the first Monday in March next and that the selectmen provide a rope for said bell and let out the ringing the bell to some person in that way they shall think best.

A word about the name of our church as it appears in town records. When first established in 1733 it was the only church, so needed no name. It was simply “the church.” In formal documents it was the Church of Christ in Harvard, Mass. Town and church were inseparable. All expenses for erecting and maintaining a meetinghouse including the minister’s salary involved the town. The church managed spiritual affairs, admonished non-attenders, arranged for communion, etc., and selected a minister – this last needing confirmation by the town in town meeting.

In 1775 the Baptist Society was organized. So far as church and town were concerned it made little difference. According to the constitution of the Commonwealth, adopted in 1780, they could no longer be required to pay a tax for the support of the town minister and were therefore exempted without any argument or rancor. They still had to pay their share of the upkeep of the town house. The records of the 1806 period show mention of the Baptist church, the Shaker, the Methodists and “the church.”

In legal documents, deeds, maps, etc., the meetinghouse had to be defined. As the Baptists had a meetinghouse also, the name Congregational Meetinghouse was applied to the first church building, a name used state-wide for the town church. This is not generally understood by the present generation, as the Evangelical branch have been popularly known as the Congregational Church.

I was riding through Lancaster recently with a friend who is Unitarian but not from New England. She thought our Harvard Congregational Unitarian Church must be a union church. I tried to explain that we were the original Congregationalist Church and Congregation had nothing to do with doctrine. I don’t know whether I finally got it over to her, but just then we went past the First Church of Christ of Lancaster, Mass., which I pointed out to her. She was more confused than ever.

The Baptists and Congregationalists managed to maintain a peaceful co-existance. When a Methodist Church was added it caused no noticeable disturbance. Both societies and the Shakers also demanded to be exempt from paying for the steeple. It was voted to deny their request but they finally got their way.

By 1820, another sect had appeared known as the Universalians. There are no records of this society extant. We don’t know if they were the same society that had met formerly in Still River or a new organization, but they were a bunch of roughnecks. They took over the town meeting and voted down the appropriation for the Congregational minister though they were not expected to pay it. They ordered that the bell be not rung, then amended this that it should be rung at funerals at the town’s expense. The congregationalists petitioned the legislature for the right to incorporate and manage their own affairs. The town countered that the petitioners were only a small part of the congregation and the petition was denied. Thereupon the more conservative minded of the petitioners walked out of the church and founded a church of their own by the name of the Calvinistic Congregational Society, a few months later changing the name to First Congregational Society connected with the Calvinistic Congregational Society. Imagine writing that on a check. However, Congregationist in the town records at this period refers to the first church, us, and the new church is called Calvinistics or Calvinists.

In 1821, the Congregationalists were given permission to set up a stove. No money appropriated so I suppose we did it at our own expense. The town did vote to buy two cords of maple wood for it. But it is on record that the town had the use of the stove at town meetings. There was no chimney. Where did the smoke go?

In 1828, it was pointed out and confirmed by court decisions in other towns that the town had no longer any right to the meetinghouse, so no further records concerning it occur in the town record.

One of the first acts of the new church after separation from the town was the purchase of a new bell. March 12, 1827, — to see if the parish will do anything about disposing of the bell on said meeting house and procuring another bell. Voted that the prudential committee of said parish should ascertain what the bell is worth and also what will be the expense of a triangle and report at a future date. September 10, 1827, — heard the report of the bell committee that Mr. Paul Revere of Boston would take the old bell and furnish a new one by our paying him ten cents per pound on the weight of the bell and 5 percent discount for cash. To obtain the money by subscription. It was over subscribed.

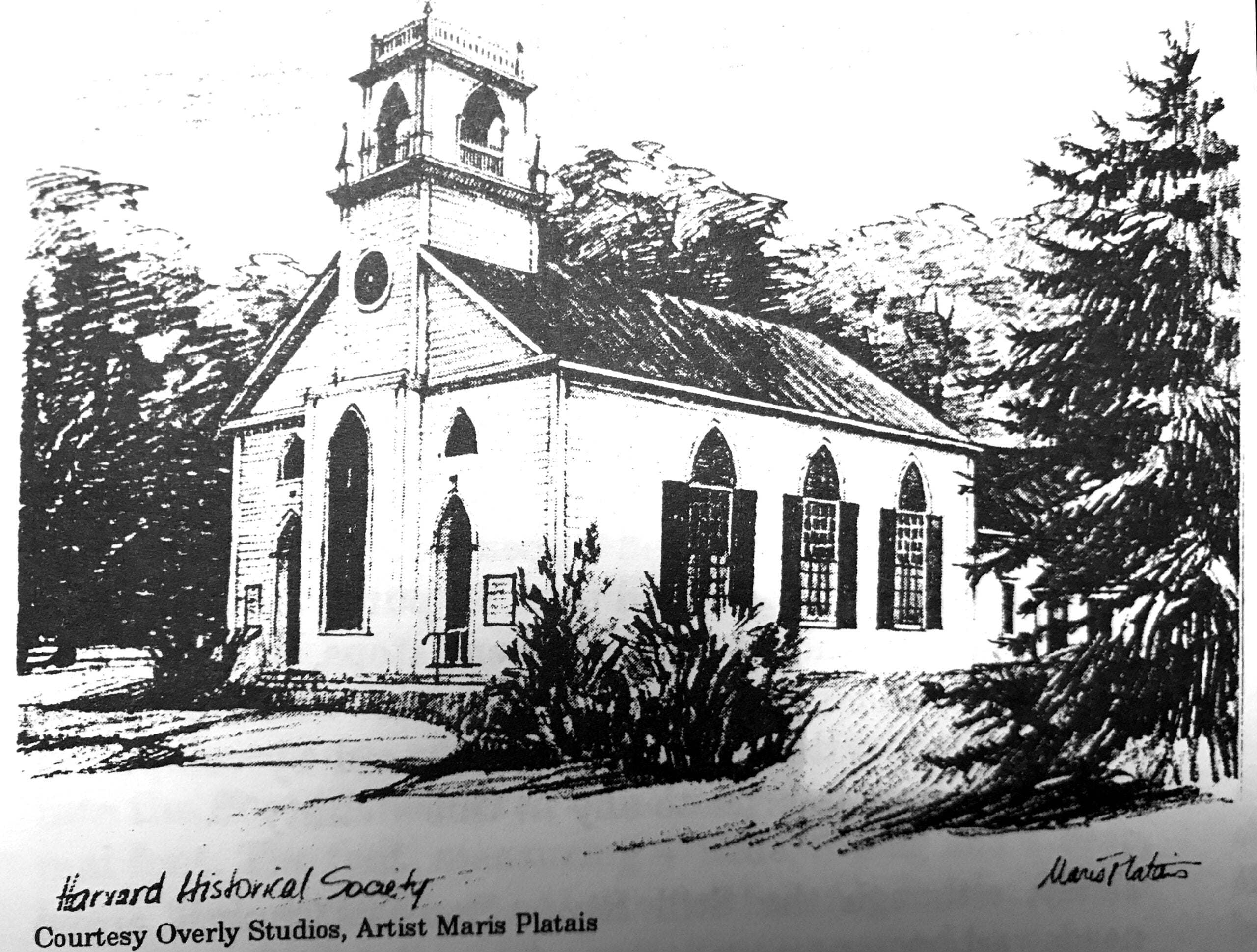

March 9, 1840, — voted to raise a committee of 12 to take into consideration the expediency of building a new church. The Rev. George Fisher’s society tendered the use of their meeting house during the building of the new house for which act of Christian fellowship the parish voted their thanks but preferred to use the town hall. The cost of the new building was $2,240.98. Insured for $2000.

Things were not always sweetness and light, however. In 1855, the church across the common decided the name of their organization was too long and cumbersome as it certainly was, and decided to change it. The name agreed upon was Evangelical Congregational Society, the name they still bear. I have not seen the records of this society but there may have been some argument about the name which leaked out for the Congregational Society, us, formally voted at a parish meeting that as the Ecclesiastical records of the Church previous to the with-drawing of a number of persons to worship in another church, show that this (the First Congregational Church in Harvard) is the true and ancient name of this church and that we have not forfeited it by any act of omission or commission, therefore, we resume our only true name, namely The First Congregational Church in Harvard and order the same to be recorded this third day of May anno Domine 1855. But the parish clerk will refer to it as First Parish.

A peculiar vote on September 2, 1861—we will not authorize the exchange of our present bell—but they must have done so. As you know, the present bell is not the Paul Revere bell. It might have been nice to boast that we had a Revere bell, but if the bell had not been exchanged, all we would have had now would be a lump of metal. This same year the members of the struggling Universalist church were invited to join with us. This is not the unruly crowd of 40 years ago, but a different organization. They accepted the invitation and were quietly absorbed. The Universalist minister occupied our pulpit on at least one occasion.

In 1867, it was voted to consider plans for remodeling the church, but there were insufficient funds. The project was revived in 1869 with the following report from the committee, that they had examined the church at Still River and think that our gallery should be partially removed and a platform built for the choir. Six pews taken from below, but there would be pews in the gallery in the plan contemplated. Six pews would be destroyed at a cost of $350.

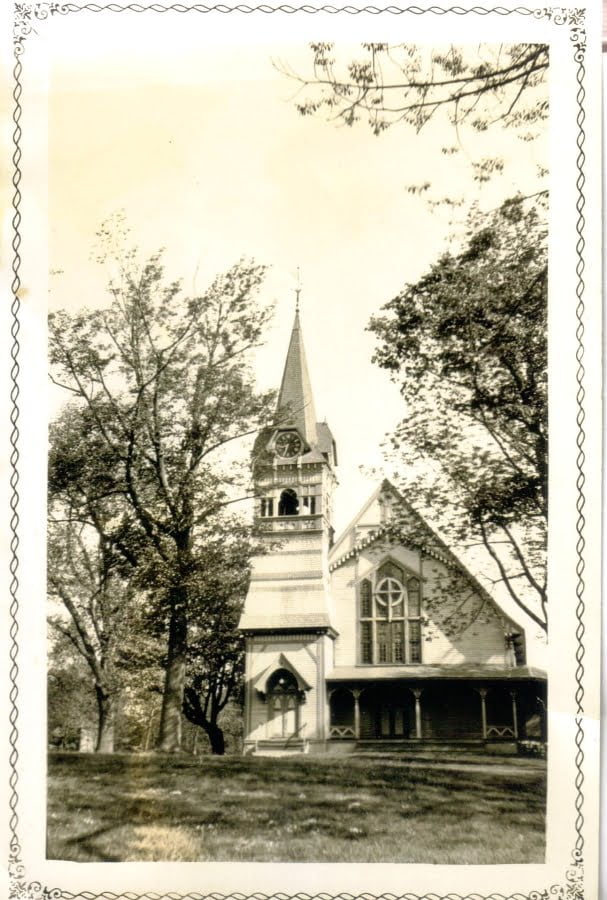

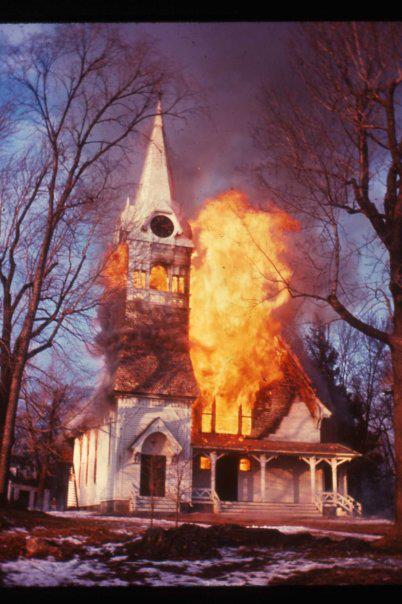

February 18, 1875 – voted to build a new meetinghouse. That’s all. Of course, we all know what happened in February of 1875, but what a bald way of recording it. The new building was to resemble one in Hyde Park. A list of subscribers from out of town might be of interest. Grafton, $30.55; Worcester, $170.50 (Worcester had recently lost her minister, Alonzo Hill, who was a native born Harvard man and had been prepared for college under the tutelage of our minister, Stephen Bemis); Lancaster, $125; Lowell, $100; First Church of Boston, $130; Waltham $30; Northboro, $29.75; Clinton, $80; Chelmsford, $25; Brookfield, $30; Marlboro, $11; Northampton, $40.50; Bolton, $20; Templeton, $25; Littleton, $43; Somerville, $100. Small amounts to be sure, but the whole cost of building was only $9,838.01, and what with the subscription in town, the insurance and individual subscribers, one old anonymous lady aged 84 years gave $2.00, the amount was oversubscribed by $76.32.

I do not have any specifications for the new church but you all must remember it. The steeple was raised to admit the town clock, the chancel was enlarged at one time and the parish rooms with the first flush toilets ever in any of our churches. The furnace gave trouble from the first, had to be replaced right away for not heating the church and was repaired several times. A larger furnace involving excavation of the cellar was installed in 1891 but the furnace came out the victor in the end. The church was wired in 1912 and there were various items concerning painting, shingling, etc.

This brings us to 1967. About the structure and shape of our present building, I have little to say; you can see for yourselves, or if you don’t want to take the time today, drop in some Sunday morning. You will be very welcome. But to compare it with the first meetinghouse, I have said that it was about the same size – that is, just the auditorium without the ancillary rooms in front and rear that are so necessary to a modern building and make the size just about double.

We have enough toilets to take care of an epidemical emergency. The first three buildings had none. What on earth did they do? There was no wee small house out back.

There were two services each Sunday in Harvard, the length of which is not stated, but elsewhere often of four hours each with a nooning in between. We have our coffee hour. Have you ever stopped to think what a blessing that would have been in the early days? Alice Morse Earle in her book “Sabbath Day in Old Colonial New England” states that only men were allowed to repair to the tavern, in this case the house on the corner where Mrs. Beebe-Center lives – it was built for that purpose, but this seems inhumane. Surely the women would be allowed the use of one room where they could imbibe hot rum, not coffee. But Mrs. Earle is an authority; she ought to know.

We also have heat in our building. It is said that in some churches the people took their dogs with them so that they would have something warm to put their feet on, but the dogs refused to conduct themselves in a manner seemly to the Sabbath and took to fighting just as the church members did on numerous occasions, though not on the Sabbath and not physically, and had to be put out – that is the dogs, not the people. Then little foot warmers were introduced and many a church is said to have burned down through an overlooked or forgotten warmer.

There is a lot of plywood in the construction. Plywood is one of the greatest modern inventions, it is so biddable, can take an enormous amount of stress and strain and is so light. It is actually a sandwich, a think 1/8 inch slice of wood running lengthwise, another crosswise and a third lengthwise again. The first church had pitch pine, also something simply called boards. The new church has boards also, but the floor is specified oak, subfloor plywood. The wall-to-wall carpet hides the oak but I swiped a small piece during construction so there will be a sample to show next time we burn down the church. Oh yes, we do have pine risers on the stairs, and a morgan goose neck; what is a morgan goose? The new church has siding that I first read as horiz plush—plush boards? It didn’t seem sensible so I finally settled for flush to match the toilets. But what in the devil is horiz?

Nancy Case has very kindly allowed me to examine the working plans of the church which I have here. My admiration of Nancy has gone up a peg since I looked at them. One must be a cryptogramist and cuneiformologist to make them out. But go look for yourselves.