The Baptists of Still River

Their Church and Their Time in Harvard History.It was June 27, 1776, the week before our Declaration of Independence. Our forefathers were in their final hours of finishing that historic document and no doubt reviewing the details of their strategy. In Harvard, although spring had turned to summer, this was not to be the ordinary, quiet Harvard summer. The American revolution was in full swing and the townspeople were preoccupied with the war if not also directly involved in it.

Undaunted by these times, Dr. Isaiah Parker, an energetic, 24 year old physician, chose this moment to lead 14 people from Harvard’s established church to organize a Baptist Society. This precedent-setting action by the Baptists was worrisome to the townspeople since the “First Church” had served as the town’s only church and was supported by all residents through assessments by the town. Although freedom of religion was well established, most inland towns worshipped in their town-owned churches. But regardless, this action by the Baptists changed the status quo that would eventually lead to the separation of church and state in Harvard.

The Baptists continued their support of the First Church as they worked on establishing their own. Their success was enhanced by the great distances to other Baptist churches in the county and the influence of their prominent membership. They acquired property for their church in Still River and around 1782, they purchased at an auction a 30-year-old Leominster meetinghouse which was to be razed. The Baptists moved the building and reassembled it on the site, and with Dr. Parker as minister, went on to prosper for some 20 years, gaining 174 members. In 1798, however, Dr. Parker converted to the Universalist faith and announced his conversion six years later. One of his founding colleagues, Deacon, William Willard Jr., died in this period and was buried at the Meetinghouse in 1795. His grave, the only one at this site, is maintained on the southeastern corner of the Meetinghouse’s original property.

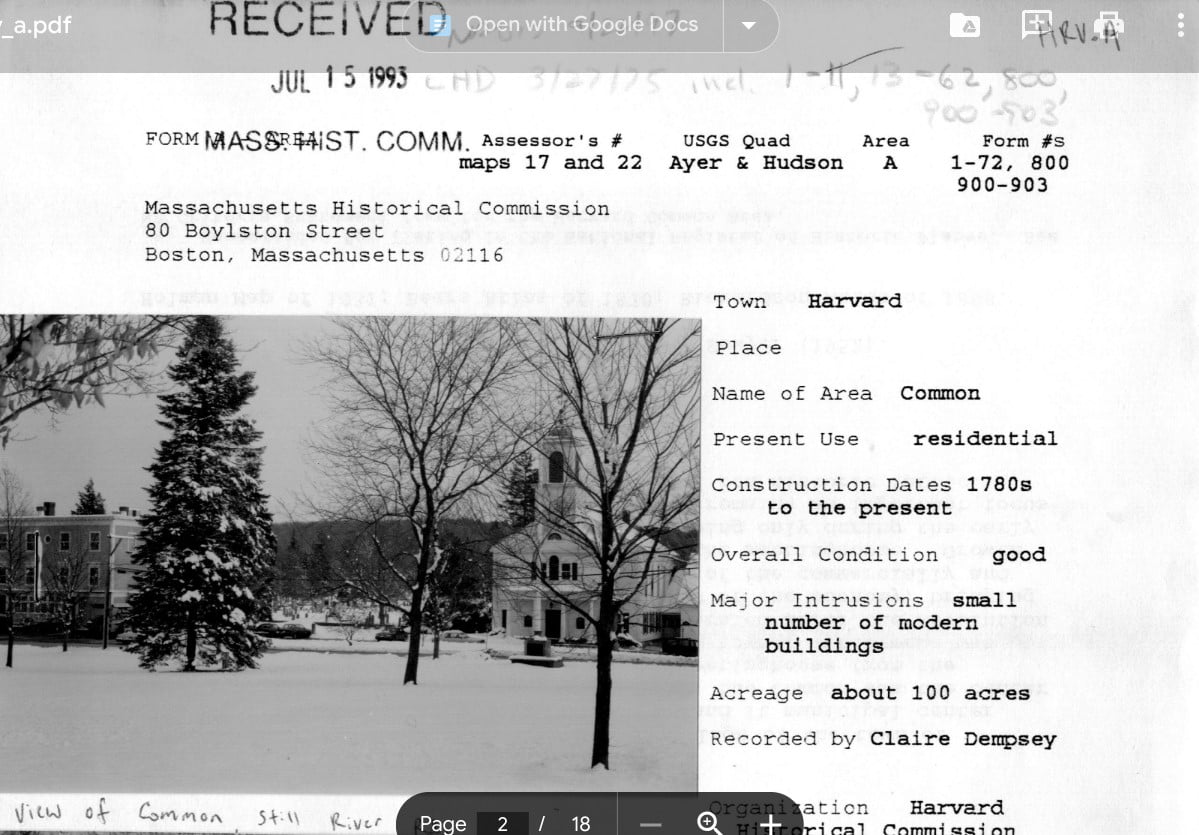

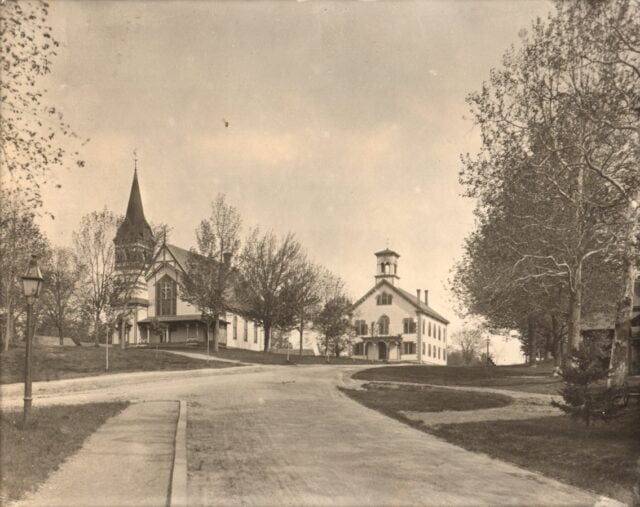

By 1800 there were five churches in Harvard: the Congregationalists, Baptists, Shakers, Methodists, and Universalists. That year, the Shakers asked to be excluded from an assessment by the town for the First Church. In a key decision, the town declared the assessment unconstitutional, thus paving the way for the official separation of church and state. Finally, in 1821, the First Church split into two: the Unitarian Church and the Evangelical Congregational Church, and in a separate action, the town went on to build a town hall in 1828. The de facto separation of church and state in Harvard was thus realized.

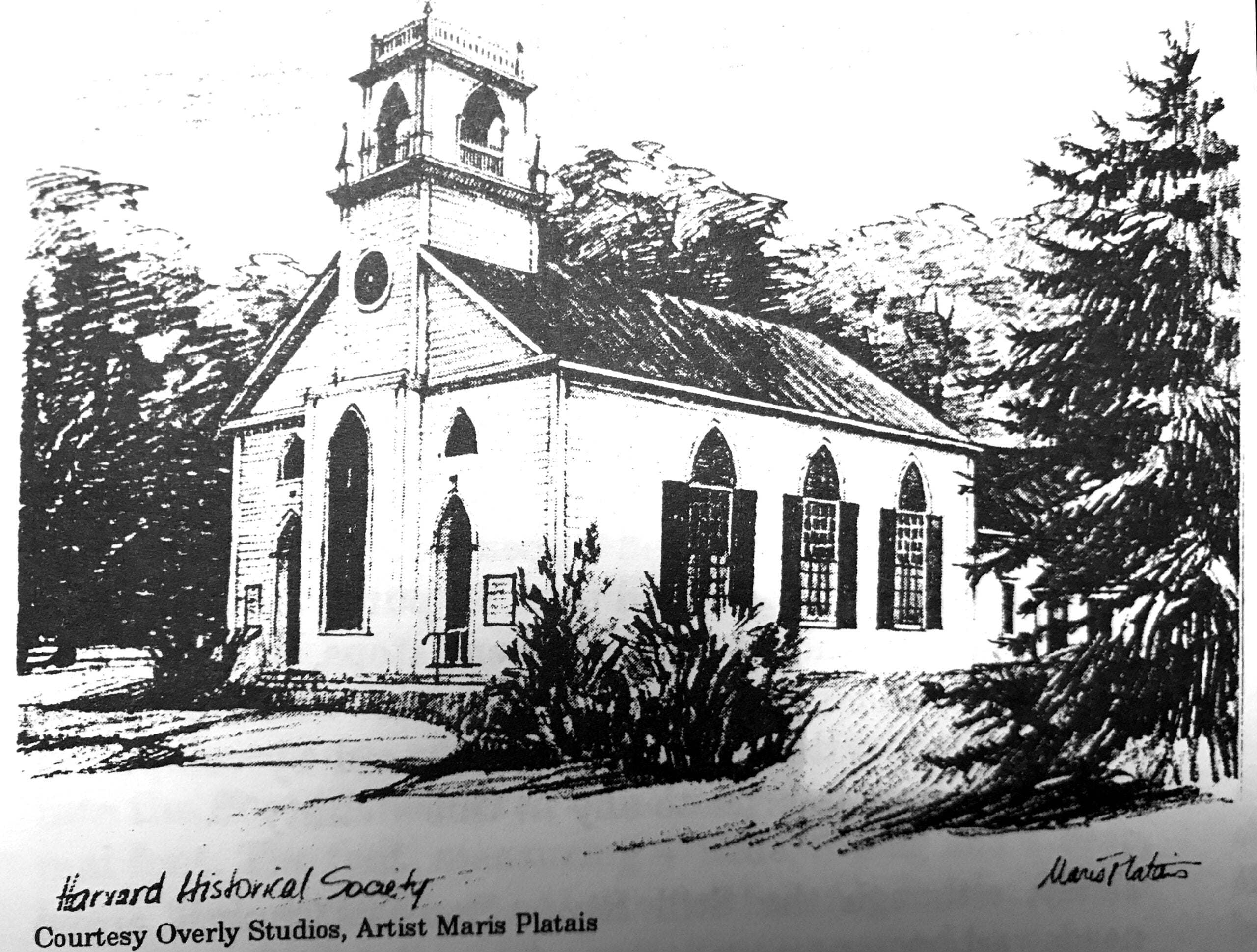

During this period, the Baptist community grew rapidly as did that of the Shakers. To accommodate this growth, the Baptists voted on 22 October 1832 to build a larger meetinghouse. In preparation for the construction, they moved the old Meetinghouse across the road and converted it into a parsonage. The new Meetinghouse, measuring 42 by 39 feet, was built on a granite and stone foundation “a few feet nearer the street.” It was designed with a Gothic theme in its windows and doors, a square steeple, and a lofty, coved ceiling inside. As it stands, it is brightly lighted with a solar orientation that allows the sun on the southern exposure through three of its six great, double-sash windows. Today, those ancient windows still hold most of their original panes. The old, double-tiered shutters on the interior were closed to filter sunlight in the summer or keep out those drafts from the north in the winter. To the rear of the Meetinghouse was a balconied choir loft, behind and above which was a large clear glass window overlooking the village of Still River and the Nashua River Valley. The window was centered between the two front entrances, each of which is capped with shuttered Gothic arches. The entrances hold heavy double doors with deep Gothic arch carvings on the outsides. To the east, the Meetinghouse may have had a window over the altar similar to the west window.

Although the Baptists were accustomed to a heated church, the Meetinghouse was probably originally unheated. For the minister, a high pulpit was crafted that was reached by stairs. The congregation was seated in pews organized in three rows: two on the outsides and a double-wide row in the center to define two aisles. The aisles guided the congregation towards the Sanctuary from the entrances. The old pews which are still standing today, show the wear of more than 160 years of baptisms, marriages, final prayers, and weekly services by its congregation of nearly 200 adults and their children.

The bell, acquired by some Baptist members, was cast in 1807 by George Holbrook in his Brookfield, Massachusetts, foundry, west of Worcester. The bell is properly signed with the name and location of the foundry and the year of casting.

The bell is mounted on a wheeled yoke that shows much need for restoration. A wheeled yoke allows a bell to be rung in “peal” (that is, swung back and forth), creating those joyous variations in the ringing of the bell. In addition, the clapper must be attached inside of the bell on a mount that is forged as part of the bell. In this case, the forged mount for the clapper is missing and instead, the clapper is attached to a separate iron A-frame that is mounted on the belfry floor and extends up into the bell. The bell rope is attached to the free end of the clapper to ring the bell once with each pull. This method of mounting a bell produces a “toll” which is a less joyous and somewhat monotone ring produced by holding the bell stationary and pulling the clapper to strike the bell. The toll is traditionally used to commemorate somber occasions.

But the current mount of this ancient bell is an enigma in that while the wheeled yoke hints that the bell was once rung in peal, its mount limits the bell to tolling. It is possible that the wheeled yoke was deemed unsound and the bell was modified to its present configuration. Or, it may have been cast as a tolling bell but mounted on the only available mounting which happened to be a wheeled yoke. Nevertheless, the bell is functional and is rung on special occasions. In fact, it has been said that certain Still River youths in the early 1900s climbed the belfry to ring the bell on the evening of the Fourth of July partially as prank but no doubt also in jubilation.

It is recorded by Nourse that in 1867, the Baptist congregation voted to build a vestry on the east side of the Meetinghouse measuring 22 feet in width, 32 feet in length and 12 feet in height. If there was an east-facing window over the altar, it was removed at this time to accommodate the wall between the new vestry and the main church, which also underwent its first renovation at this time. The chimney, on the wall that is common to the main church and the vestry, is shown on the Richards map of 1898 but could have been added in 1867 to accommodate a furnace for central heating. If the original construction of the Meetinghouse included an east-facing window over the altar, the chimney certainly could not have been there prior to 1867. The abandoned old furnace still in the cellar today, is to the rear of the church far from the chimney.

In apparent conflict with the recorded 1867 improvement, a post-Civil War map (1870) of Worcester County does not show the additions to the new Meetinghouse at that time. It further shows that the rear Baptist property included the cottage and an outbuilding, the origins of which no record has yet been found. If the cottage was there before 1832, it was probably used as the parsonage. The Richards’ map shows the church on its parcel as before, and on the rear parcel, three outbuildings and the cottage belonging to the Baptist Church. One of the three outbuildings on that map may not have been a separate building but actually the map-maker’s technique for showing the vestry addition.

At first, the Meetinghouse had a small organ up in the balconied choir loft. In 1870, William Bowles Willard, clerk for the Society for 57 years, presented to the Baptist Society, a new pipe organ estimated to have cost $1000. The organ was built by George Stevens in his factory on the corner of Fifth and Otis Streets in East Cambridge. Stevens was a conservative Boston organ builder who built one and two “manual” organs for churches throughout the country. The Christ Church in Cambridge purchased an organ from Stevens in 1845 to replace its Snetzler organ that had been damaged during the Revolutionary War. The thought that George Washington had heard the old Snetzler pipes inspired Stevens to place an occasional wood pipe from the old Christ Church organ among the stopped diapasons of his later (1850-1880) instruments. The Snetzler pipes, when installed in Stevens’ organs, were suitably inscribed for posterity. Stevens’ organs were distinguished in sound and appearance as noted by a contemporary critic who said, “In purity and richness of tone, as applicable to the different stops, or to a great variety of combinations, as well as to the whole power of the instrument, this organ is pronounced by competent judges to be not inferior to any in this vicinity.”

Today, although the Still River Baptist Church organ needs restoration, it still plays a beautiful hymn. It is a single manual instrument with 15 stops and an attractive five-sectional federal pipe case that extends almost 30 feet to the ceiling. The pipe case has a dark mahogany finish and is capped with a fretwork that signals the Victorian era. The instrument was hand-pumped by a dedicated member of the congregation whose working place was in a closet off the north front entrance foyer. Aside from being the coldest corner of the church in the winter, the location of the hand pump was some distance from the organist and was such as to require precision coordination between the organist and the pumpman. Indeed, were the pumpman to lapse into some “inattention” at the start of a hymn, the organist would take desperate flight or send a messenger to the tiny closet to wake or alert the errant pumpman. The old pump handle is still in place today.

Since the Stevens organ was much larger than the original organ, major alterations were required to accommodate the new organ. The rear of the church was modified to take out the center half of the choir loft and then closed with an oval wall which dramatically highlights the organ pipe case. The two sides of the choir loft and front entrances were closed with flat walls. Today, the choir loft pews may be seen behind this wall in what is now the “attic” at the foot of the belfry. These modifications also required the ceilings to be lowered in the entrance foyers which obscures the interior Gothic upper sections of the doors. With these changes, the choir was brought down to the level of the organ manual at the rear of the Meetinghouse.

Unfortunately, with the organ taking up so much room in the center rear of the church, it created a massive obstruction to the great window overlooking the valley. With no recourse, the window was covered and the outside shutters closed. Except for a brief inspection during the 1987 renovation which found the window in good condition, the windows have been kept shuttered for these last 125 years.

Across the road, the old Meetinghouse, now parsonage, was used by the Baptist minister until the Baptist Society exchanged it with William Bowles Willard for his house which was next door to the north. The Richard’s map shows the parsonage (and barn) as being immediately north of the W.B. Willard house (and barn) showing that the exchange had already taken place by 1898.

In 1902, the Meetinghouse was again enlarged to the east to accommodate a chapel and larger audiences for plays, recitals, and other functions. It was separated from the vestry by a wide, pull-down, counter-weighted pocket door. Since the vestry extended near the rear property boundary, this addition required more land which was added to the Meetinghouse parcel. Aside from being used by its members, the Baptists opened the chapel as a reading room for the Camp Devens soldiers during World War I. This addition further included an ell to the south providing a kitchen, the minister’s office, and a country toilet stack.

Although there is no record of this change, a unique aspect of the sanctuary was added in 1902: a tub was recessed into the floor of a raised section of the sanctuary and used as a baptismal font. The font, measuring 4′ wide, 8′ long and 4′ deep, has a 3′ closure to cover the font when not in use. On the morning of a baptism, the water was warmed by convection heating from a small (24″ high by 12″ diameter) pot-belly stove. It was during this period that the high pulpit was replaced with the present movable pulpit, and, when the newly-formed Harvard Gas and Electric Company brought electricity in December 1912, a motor-driven bellows (still functional today) was installed in the cellar for the organ. With electricity available, the Meetinghouse was wired and new lighting was installed. And, with all of these modern conveniences, the pumpman was happily relieved of his duties.

On Thanksgiving night, November 1910, the Wendell B. Willard house (previously the old Meetinghouse) was destroyed by fire which started in the barn that had been recently filled with hay. The house was quickly rebuilt on the site of the old barn, with the new barn to the northwest. Both still stand today at 210 Still River Road.

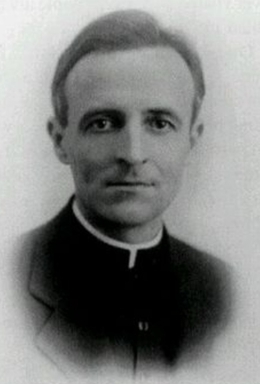

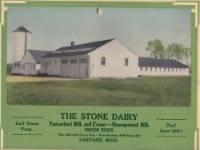

On a sunny day in June of 1915 during World War I, a member of the Baptist Society, Mr. William Gussman, set up easel and paint on the south side of the Meetinghouse by the kitchen ell to paint a small portrait of the white parsonage across the road. His painting session was interrupted when former President Theodore Roosevelt stopped by on his way to Groton to attend his son’s graduation at the Groton Academy; an event which the artist duly noted on the back of his painting. The artist later served as minister from 1919 to 1924. The painting was recovered 71 years later by the Historical Society. The subject of Reverend Gussman’s painting (which had been the old Bowles Willard house, now 216 Still River Road), went on as the Baptist parsonage until April 10, 1939, when it was sold to Mr. Michel Aubin. It has been privately held since.

On the parcel to the rear of the Meetinghouse, horse sheds were built around 1900 that were later razed in 1924 by the Baptist Society. Although research is still in progress on this point, the cottage on the rear parcel is believed to have been occupied after World War I by a single woman who was a weaver and later in the 1920s by the Scott family. After World War II, the rear property which included the cottage and garage was sold to the Watt family. While an outbuilding has been shown to exist on the site of the present garage since 1870, the building was either replaced or renovated sometime around 1920. The electrical fixtures, stucco interior finish, architecture and wood trim dates the building to that time.

After the Civil War, life in Harvard began changing and by 1900, three churches had disappeared or were fading. The Universalist and Methodist churches disbanded before the Civil War, and the Shakers left Harvard in 1918 during World War I. By 1940, although the Baptist Church was still active, it had a much smaller congregation. During these years, some members had moved to other Baptist churches in the surrounding towns, which decimated the Still River congregation and left it with little support. And, as if to test the Baptists, the infamous Hurricane of 1938 inflicted some damage on the Meetinghouse: window panes were broken, the ell was unroofed by a tree, and a fine elm tree and Christmas tree were lost. To reduce costs, the Baptists arranged to meet with the Evangelical Congregational Church in Harvard in an ironic return to where it all began. During this time, the two congregations used the Meetinghouse for musical and religious functions.

And so, the Baptists were forced to dissolve their Church 190 years after Dr. Parker convened the founders. In that time, 27 pastors ministered to the Society including a licensed female minister during the Women’s Suffrage period. The church was sold in 1966 to the Harvard Historical Society to be kept as a museum, and the remaining assets were left to the Andover Theological School and other charitable organizations. The words of Jennie Brown Willard (Mrs. Wendell B.) in 1941 best capture the spirit of the Baptist Society at that time: “We are few in numbers, but still carry on, and as long as there is a church here we will have hope.”

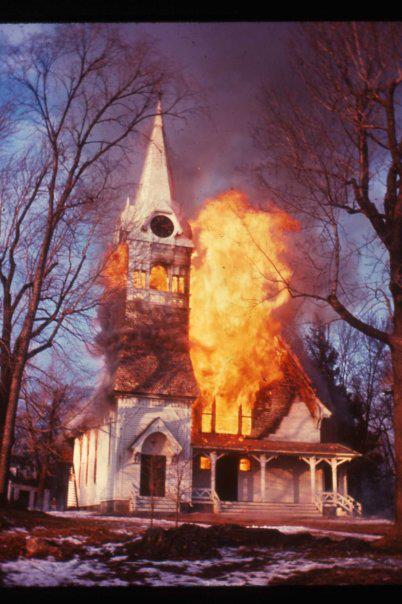

Today, maintained under the trusteeship of the Historical Society, the Meetinghouse continues to be used by the Episcopal Church of St. Alban’s, and is thus the oldest active church in Harvard. The others suffered tragic losses by fire: the Congregational Church on July 29, 1940, rebuilding March 30, 1941, and the Unitarian Church in 1875, rebuilding and burning again in 1964 to be rebuilt again. In 1987, the main church interior of the Meetinghouse was renovated for the second time since its construction. Brass period chandeliers were installed to replace the lighting installed in 1912. The Victorian fretwork crest atop the organ pipe case was recovered during these renovations and reinstalled. In the vestry, lighting was installed to illuminate the Society’s collection.

Following the renovation of 1987, the Historical Society posthumously rededicated the vestry as the Sturdy Memorial Hall, or “Sturdy Hall”, in honor of Winnifred Sturdy, past president of the Historical Society. Today the Harvard Historical Society uses the main church to present its historical programs. Also, the Society has placed on perpetual display in the main church the early pewter flagons, plates, cups and glasses of the Baptists’ communion service, some pieces of which were made in Boston. Every Sunday, the Episcopal Church of St. Alban’s holds services making full use of the main church and its Stevens organ. The Society also uses Sturdy Hall as its museum, displaying its collection of furniture and fine paintings bequeathed to the care of the Society by past residents of Harvard. The Society’s collection is displayed on a rotating basis to make available to its membership its collection of over 6,000 artifacts and heirlooms of Harvard history.

On the rear parcel, the cottage had been the residence of Miss Amy Watt for several years when in October 1992 it was sold to the Historical Society with the garage and 4.5 acres of wooded land and stone fences. Today, the rear parcel has been recombined with the front Meetinghouse parcel into a single parcel for the first time since the 1700s. The cottage has been renovated and will ultimately be used as a period house and museum. Also, the garage has been converted into a new Curator’s Quarters that will include a controlled-environment storage facility for documents, paintings and other perishable artifacts. The Society’s new grounds in that quiet, pastoral Still River setting promises many possibilities for gardens, arboretum, or conservation park to be enjoyed by the people of Harvard and generations of their children.

Written by J.R.Theriault, president, Harvard Historical Society September 16, 1993

NOTES: The founders: Stephen Gates, Tarbel Willard, Dr. Isaiah Parker, William Willard,Jr, Josiah Willard, Joseph Stone, Ruth Kilburn, Sarah Willard, Elizabeth Gates, Huldah Edes, Sarah Kilburn, Jemima Blanchard, Rachel Willard, Annis Willard. The townspeople had been concerned for a time that the Baptist leanings of the Still River folk would produce a splinter group. Henry Willard, settler of Still River was influenced in his Baptist faith by his mother, Mary Dunster, third wife of Major Simon Willard. Her father, Henry Dunster, first President of Harvard was forced to resign because of his Anabaptist convictions. While the Baptists were fervent in faith, they were community-spirited and seen as balanced in their conviction. According to Nourse, though their Puritan origins lead them to be critical of others, their zeal was seen as well-balanced and respected. In his early years, Dr. Parker owned a large landed estate which bordered the northern and eastern sides of the Meetinghouse site. It is probable that the land for the Meetinghouse came from that estate perhaps bequeathed. The coordinates for the site as located by the Massachusetts Astronomical and Trigonometrical Survey are: 42o 29’29” 22 latitude, 71o 37′ 24″ 63 longitude. The only dated reference to the raising of the first Meetinghouse is in Ref 36, page 19, a monograph on “Still River” by Morrill G. Sprague. There is no other dated record of this auction due largely (according to Nourse) to Dr. Parker’s “meagre records…which yield few facts of historical value.” Nourse does note that a chimney was added in 1822 for a stove. The Deacon was unfortunately stricken with alcoholism and excommunicated on February 21, 1791. He died four years later. Actually, the Still River congregation had shrunk to 111 in 1824 from about 200 members in 1798. In founding societies in Acton, Ayer, Bolton, Clinton, Fitchburg, Leominster, Littleton, West Boylston and West Townsend, they lost members to each congregation. However, the Baptist community as a whole grew during this period and the Society continued as a major influence in New England and the Worcester Baptist Association. If as Nourse records, the Baptists voted to build in 1832, the actual completion of the church may not have been until 1833. The old Meetinghouse was moved between the 1831 residences of Wood & Atherton, and of Dr. E.Stone as shown on the Silas Holman, Map of Harvard. The apse in ancient Christian architecture, is the semicircular end of the church that encloses the sanctuary and altar and is always oriented to the east. In its orientation, i.e., with the altar to the east, the Still River Baptist Meetinghouse conforms to the ancient architectural traditions that go back to the Carolingian period of the Middle Ages. Whether this was intentional or accidental, we will give the Baptists the benefit of the doubt. A stove with chimney was added to the Meetinghouse in 1822. The sanctuary of a church is the area occupied by the clergy and excludes the general area of the congregation. See Ref 25, Some Fires Which Have Occured Since 1894 And A Brief Description of a Few of the Buildings, p. 17. See Ref 25,Eccleasiastical History, Baptist Society section, p. 61. On November 2, 1988, the Society received an oil-on-board painting of the Baptist Parsonage from Rita Hess of Miami, Florida who had purchased the painting at a flea market. The painting (Accession No: H.1990.01) by W.H. Gussman is titled “Parsonage of Still River Baptist Church” and is inscribed on the back “On the Day President Rosevelt whent through to Groton to his son’s graduation”. Ms Hess estimates the date of the painting to be 1919 to 1925. Assuming that the artist’s note is correct, the last of President Roosevelt’s sons, Quinton, graduated in 1915 which sets the latest possible date to about June 1915. The artist, W.H. Gussman was Pastor of the Baptist Church from 1919-1924. Taken from Reminiscing with Edwin Haskell, Harvard Historical Society program by Mr. Edwin Haskell, September 22, 1992. The word “manual” is organ terminology for the keyboard. Based on a similar organ built by Stevens for the Evangelical Congregational Church in Harvard which cost $1080. As told by Miss Elvira Scorgie to Mr/Mrs J.R.Theriault during a visit at her home in November 1992. Stevens’ organs may be seen and heard today at the First Parish Church of Shirley Center, Evangelical Congregational Church in Harvard, St. Mary’s Church in Boston, First Parish in Belfast, Maine, the Congregational Church in Wiscasset, Maine, and St. Peter’s Church in Gloucester among others. The Ministers: 1778:Dr.Isaiah Parker;1799:George Robinson;1812:Abisha Samson;1832:John E.Lazell;1833:B.H.Hathorne; 1835:Moses Curtis; 1842:Clark Sibley; 1850:Charles M.Willard; 1857:John H.Lerned; 1861:Andrew Dunh; 1863:Leonard Tracy; 1869:John H.Lerned; 1870:William Leach; 1871:John W.Dick; 1874:Daniel Round; 1879:William Reed; 1886:James F.Morton; 1888:William H.Evans; 1895:James Brownville; 1896:Everett A.Bowen; 1900:Edgar E.Harris; 1905:Lyman Herbert Morse; 1919:William Gussman; 1924:Charles L.Pierce; 1925:Mrs. Julia W.Pierce; 1928:George E.Jacques; 1938:Howard P.Davis.(Ref:??) Conversation with Mrs. Phyllis Konop, organist for the Evangelical Congregational Church, and Harvard music teacher. The Historical Society collection includes the collections of the following residents of Harvard: A.Armstrong, E.L.S.Bigelow, G.H.Chase, C.Farnsworth, E.A.Gale, E.W.Harrod, E.E.Hersey, J.E.Maynard, Newell-Gerry, F.A.Pollard, R.B.Ross, Dr.H.B. Royal, D.G.Slade, F.H.Sprague, E.A.Stone, W.Sturdy, L.Tarlton, N.Warner, E.M.Willard, J.B.Willard, J.K.Willard. Other individuals have contributed to the ever growing collection.

REFERENCES: History of the Town of Harvard, Massachusetts Henry S.Nourse, Printed for Warren Hapgood by W.J.Coulter, Clinton,MA 1894. History of Harvard, 1894-1940 (Manuscript), Committee of the Harvard Historical Society; Ida A. Harris, Chairman; undated Directions of a Town,R.C.Anderson,Harvard Common Press,1976. The Old Meetinghouse Sanctuary, Dr. J.E.D. Humphries, Harvard Historical Society Newsletter, Spring 1990. History of the Baptist Church and Meeting House, Elvira Scorgie, undated, unpublished. The Organ in New England, Barbara Owen, publisher unknown. Boston Musical Gazette, June 15, 1849. Still River Meetinghouse, Part Two, Dr. J.E.D. Humphries, Harvard Historical Society Newsletter, Fall 1990. Atlas of Worcester County, Plates 33,36,L.J.Richards&Co.,1898. Map of Harvard, Silas Holman, 1831. Map of Worcester County, Plates 33,36, Baer,1870. The Baptist Church of Harvard-Still River 1776-1926, Katherine L.Lawrence Harvard, Massachusetts; 1732-1982 Harvard 250th Anniversary Celebration Committee, 1981.