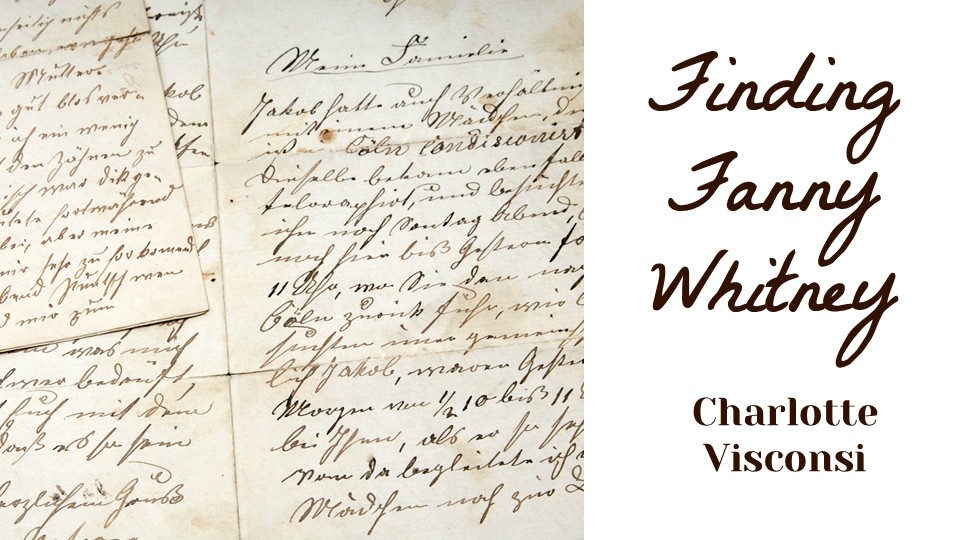

Finding Fanny Whitney: The Civil War Letters of Charles E. Whitney

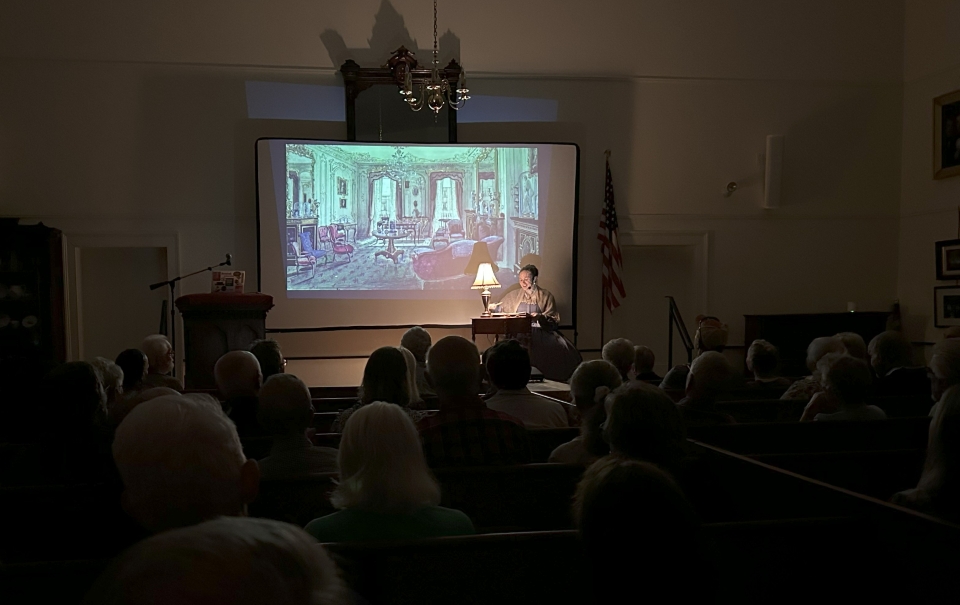

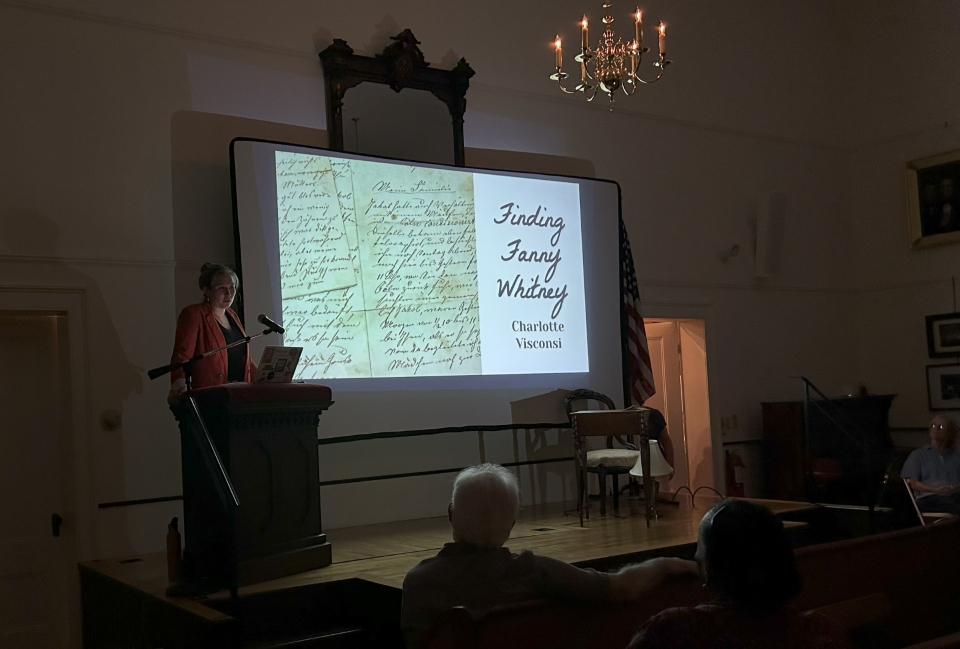

A Living History Presentation by Charlotte Visconsi.Was on

Thursday September 18, 2025

Charles went off to war in the Union Army in 1862 and served to the end of the war.

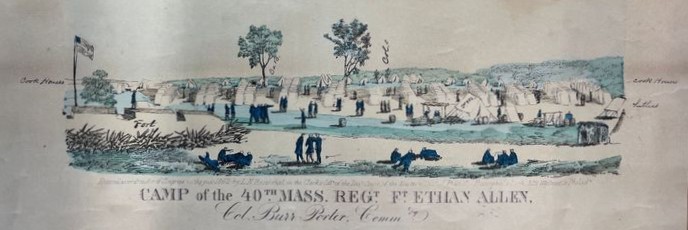

Charles Whitney 40th Mass Regiment Camp

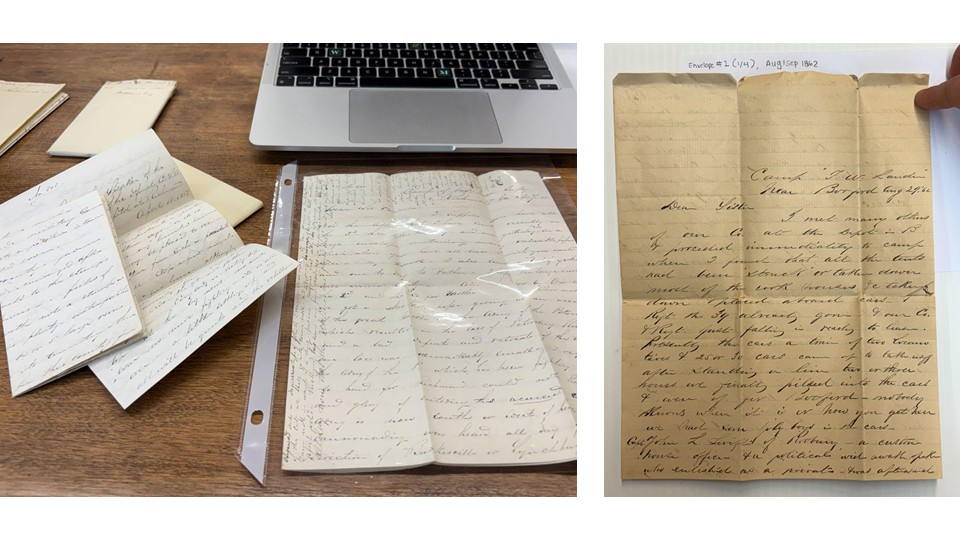

More than 100 letters written by Charles E. Whitney to his family during the Civil War were preserved by Louise North Griffin, who lived on the Common, and were donated to the HHS by Dawn Webster in honor of her mother, Louise North Griffin and her stepfather David N. Griffin, to be transcribed and published. This summer, recent William and Mary history graduate and Harvard resident Charlotte Visconsi has begun the important work of transcribing the letters.

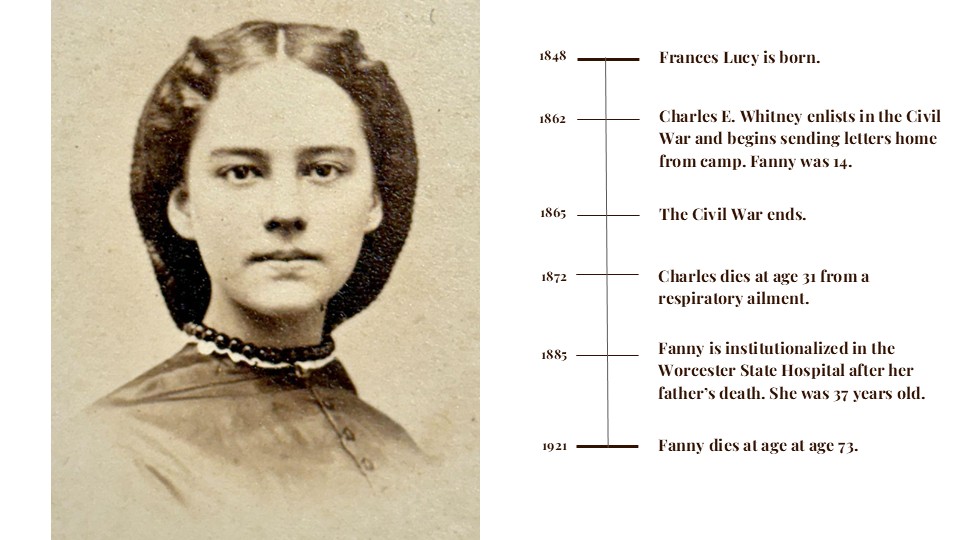

In this living history program, Charlotte portrays Fanny Whitney, presenting Charles’s early letters from the war and sharing the experiences and thoughts of a woman living at home while her brother went off to war.

Coming soon!

We will be posting several of Charles’s letters to this website over the coming weeks, featuring both the original scans and full transcripts. Stay informed through our weekly newsletter. If you’d like to receive the newsletter and join our mailing list, please register here.

Presentation Slides

Published: September 12, 2025

A young historian finds a female perspective in soldier’s Civil War letters at Historical Society

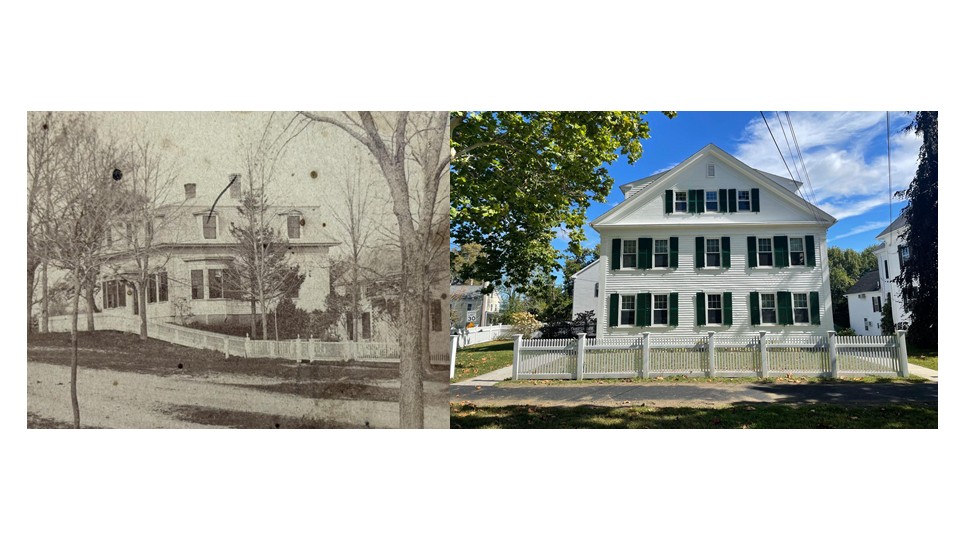

The Harvard Historical Society will present a living history program, “Finding Fanny Whitney: Civil War letters from Charles E. Whitney to his sister Frances Louise,” on Thursday, Sept. 18, at 7 p.m., at the meetinghouse, 215 Still River Road. The Whitneys were a prominent family in Harvard’s history. This summer, Harvard resident and recent William and Mary graduate Charlotte Visconsi transcribed about 25 of the letters that Charles wrote to his younger sister, Frances, called Fanny. Visconsi will talk about the process of transcription and assume the character of Fanny to read from diary entries she has written in the voice of Fanny, drawn from Charles’ letters to her.

The 119 letters that Charles Whitney wrote to family members during the Civil War were given to the society by Allen Griffin, on behalf of Dawn Webster. In an email to the society, Griffin described how he came into possession of the letters. “Charles Whitney’s letters came down through his descendants and ended up with my aunt, Louise North Griffin, who died in 2004 in Harvard. My uncle David, who loved history, preserved his adored wife’s letters. As he was dying in 2023, he gave me, as the named executor of his estate, Louise’s letters for safekeeping. Upon David’s death, the letters became the property of Louise’s daughter, Dawn Webster.” Allen Griffin said the letters were donated with the proviso that they be transcribed and exhibited.

Historian Charlotte Visconsi as Fanny Whitney. (Courtesy photo)

Visconsi, a history major, had contacted the society about whether there was a project she could volunteer for over the summer. In a recent conversation, Visconsi recalled how Judy Warner, the society’s administrative assistant, had asked her if she could read cursive and would be interested in transcribing letters from the Civil War. Visconsi realized this was right up her alley, even though early modern European history, not American history, is her area of interest. “It’s not what I do, but it’s exactly what I do,” Visconsi said. In her historical work at school, her project had been reading Spanish manuscripts to find marginalized voices in 17th-century Spain. She could definitely read cursive.

She said the letters were actually quite legible and Charles’ style is very straightforward, with only a few exceptions where he waxes quite “poetic.” There were cases where she couldn’t make out some of the words; in her talk, she will describe the methods she used to decipher what wasn’t clear.

‘The voice that’s not there’

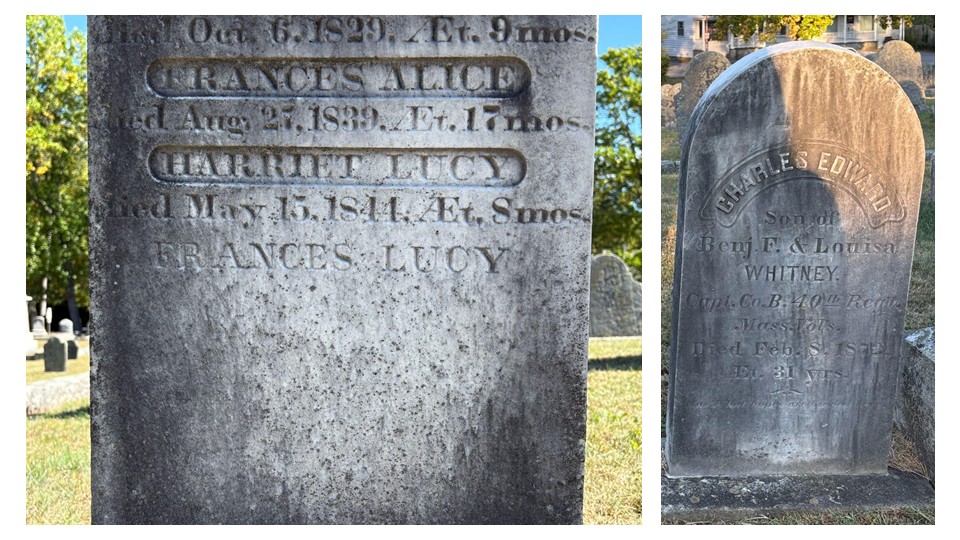

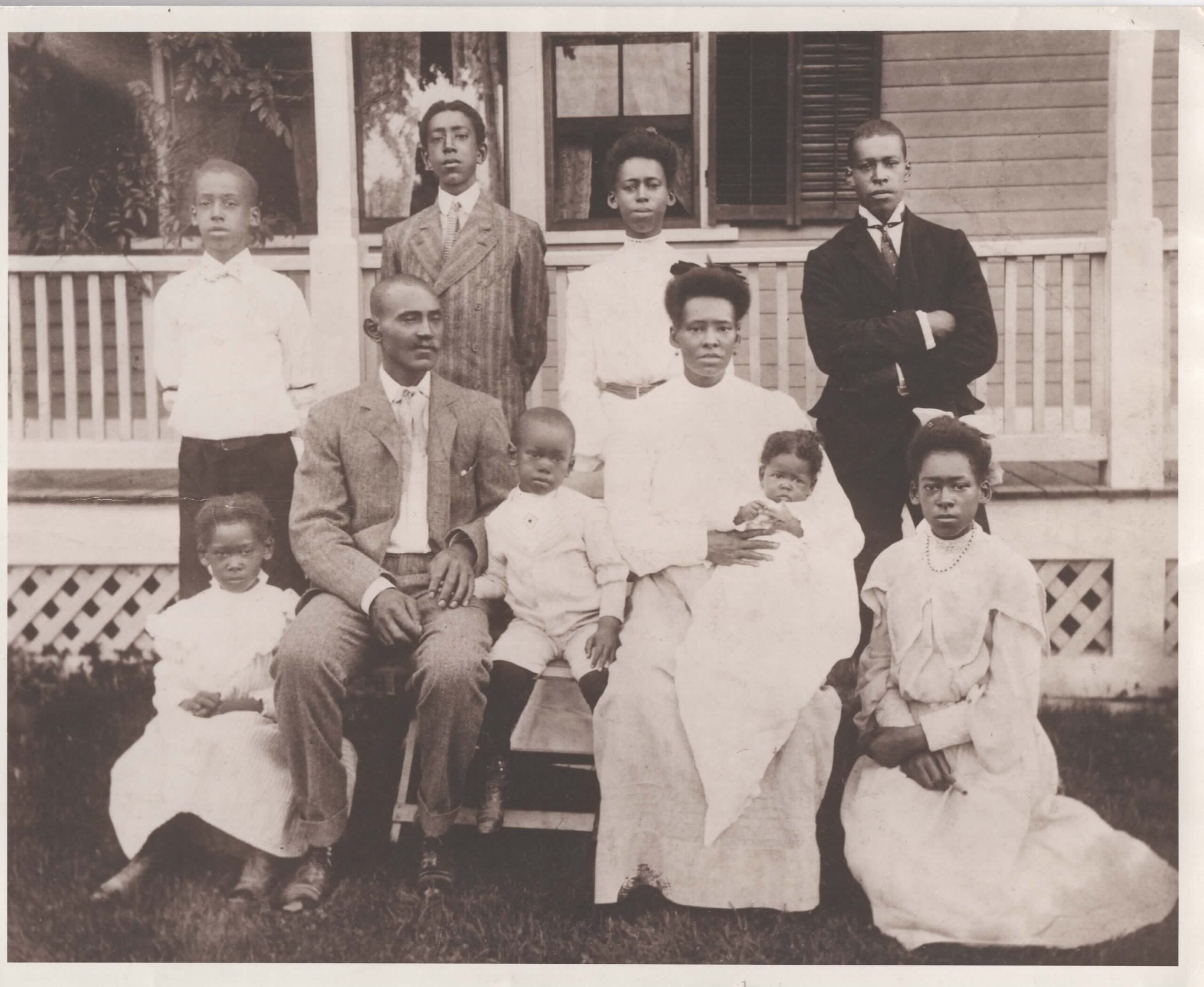

The first letter Visconsi read was to “Dear sister,” and she was immediately intrigued and wondered who this was and what her story might be. With the help of the society’s genealogist, Susan Lee, she drew a family tree and learned Fanny was Charles’ only living sister. There was little immediate information about Fanny, but with more digging, Visconsi learned that Fanny was referred to as an “invalid” at least by the time she was in her mid-20s, and she was institutionalized in Worcester State Hospital at the age of 37. Visconsi began looking for more of Charles’ letters to Fanny. She said of her interest in Fanny, “It was natural to be drawn to the voice that’s not there.”

Visconsi said that in the early letters, Charles writes about camp life in Virginia and how not much is going on. She will talk about, among other observations and conjectures, Charles’ patriotic idealism and how his response to what Fanny must have written to him shows a contrast between the male and female reactions to war. In an email, Visconsi wrote, “Fanny’s experience in 19th-century Harvard invokes a fascinating picture of life in our beautiful town during the Civil War. Perhaps more importantly, though, the erasure of Fanny’s voice highlights the tragic and often intentional marginalization of historical female perspectives.”

Visconsi, who is headed off to Oxford University this fall for a master’s degree, wrote further that she is unexpectedly sad to put the project on hold and to leave Fanny’s story unfinished. “I did not expect to uncover the rich, mysterious, and ultimately tragic voice of Fanny Whitney peeking through her brother’s words. Yet, now that I have ‘met’ her—mapped the events of her life, walked past her childhood home on the Common, seen her gravestone in our historic graveyard—I feel deeply connected to her as a historian, and as a young woman.”

In a short intermission and at the end of the talk, three musicians—Joan Eliyesil on banjo, Dave Kassel on fiddle, and David Gilfix on guitar—will play songs of the Civil War. “Soldier’s Joy” was written at the time of the war, and “Ashokan Farewell,” written in 1982, was the theme song for Ken Burns’ 1990 Civil War documentary. There will be refreshments, during which time visitors may view relevant items from the society’s collection, including Charles Whitney’s sword and his box of memorabilia from the war.

The program is free, but a donation toward the society’s further public programming is appreciated.

From The Harvard Press by Carlene Phillips · Friday, September 12, 2025

Copyright Harvard Press, LLC, 1 Still River Road, PO Box 1, Harvard, MA 01451, 2025.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

More Historical Society Events, past and present...