Fruitlands

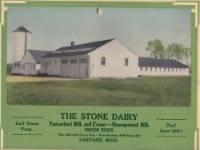

Located on 210 acres along Prospect Hill Road, the Fruitlands Museum was founded, expanded, and curated by Clara Endicott Sears, a member of a wealthy Boston family and among the best known and most accomplished of Harvard’s summer residents. Beginning with the 1910 purchase of 38 acres upon which to build Pergolas, her summer home, Sears eventually acquired most of the five historic farmsteads in the area. Her estate grew to 450 acres and included both a working dairy farm and the museum complex. Pergolas was dismantled as per her instructions after her death in 1960. Fruitlands now consists of four museum buildings: the Fruitlands Farmhouse, the only building original to the property; the Shaker Museum, the first of its kind in the United States; the Native American Museum; and the Art Museum (originally called the Picture Gallery). In addition, the Wayside Visitor Center houses classroom and exhibition space. Fruitlands was operated as an independent nonprofit organization from its incorporation in 1930 until 2016, when it was acquired by The Trustees of Reservations.

The museums’ creation and contents reflect the trajectories of Sears’ historical, intellectual, and preservationist interests, which can also be traced through her many books and other writings. At a 1930 meeting of the newly formed Board of Trustees, Sears expressed her hope that Fruitlands would be a place where visitors could “deepen their powers of thinking.” “There are many places in this country the public can meet,” she continued. “This place is not meant for recreation. It is meant for inspiration…It must always remain more or less like a poem.”

Fruitlands Farmhouse:

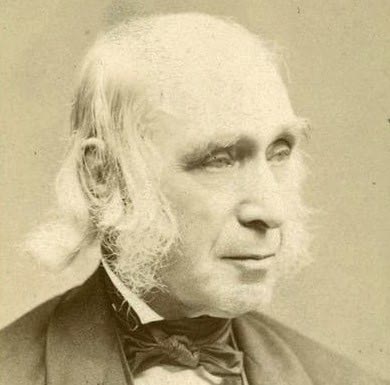

Shortly after her acquisition of the land for Pergolas, Sears discovered that an adjacent property had been the site of Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands, a failed transcendentalist experiment in communal living, subsistence agriculture, self-reliance, and spiritual growth. Originally built in 1800 by a member of the Sprague family, the farmhouse and surrounding 90 acres of land were purchased in 1843 by Charles Lane, a British educator and Alcott disciple. Alcott and Lane envisioned the creation of “new Eden” in which their “consociate family” would live in harmony with both human nature and the natural world. They described their new endeavor in a June 10, 1843 letter to The Dial, a publication of the transcendentalist movement:

We have made an arrangement with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres, which liberates this tract from human ownership. For picturesque beauty, both in the near and distant landscape, the spot has few rivals…The vale, through which flows a tributary of the Nashua, is esteemed for its fertility and ease of cultivation, is adorned with groves of nut-trees, maples, and pines, and watered by small streams. Distant not thirty miles from the metropolis of New England, this reserve lies in a serene and sequestered dell…The nearest hamlet is that of Still River, a field’s walk of twenty minutes, and the village of Harvard is reached by circuitous and hilly roads of nearly three miles. Here we prosecute our effort to initiate a Family in harmony with the primitive instincts of man.

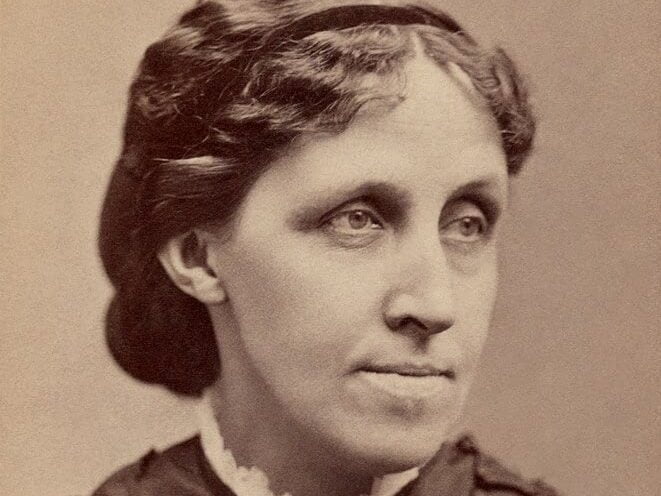

Louisa May Alcott presented a very different view of the property and its prospects in Transcendental Wild Oats, a fictionalized account of the Fruitlands experiment:

[T]his prospective Eden consisted of an old red farm-house, a dilapidated barn, many acres of meadow-land, and a grove. Ten ancient apple-trees were all the “chaste supply” which the place afforded, but in the firm belief that plenteous orchards were soon to be evoked from their inner consciousness, these sanguine founders had christened their domain Fruitlands.

The consociate family consisted of fourteen residents, including Alcott, his wife Abigail May Alcott, and their four daughters, as well as Lane and his son. They intended to eschew the ownership of private property and refrain entirely from trade, hired labor, and the exploitation of animals, including the use of manure as fertilizer. Indeed, many of the adult male residents, including Bronson, refrained from any labor at all, leaving the bulk of the farmwork to Abigail and a few others. In addition to their limited vegan diet, they consumed no stimulants (e.g. coffee and tea), drank only water, bathed in cold water, and rejected the use of artificial light. Only linen clothes and canvas shoes were permitted, wool requiring the exploitation of sheep and cotton closely linked to slavery. Their new Eden was a failure in the practical sense, surviving only some seven months and ending with the coming of winter.

Sears purchased the property in 1913, researched and restored the farmhouse, and began to track down objects associated with the Alcott family, Henry David Thoreau, the transcendentalist movement, and 19th century New England farmstead life generally. The museum was opened to the public in 1914, the same year she published Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands. The Fruitlands Farmhouse was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974.

Shaker Museum:

Sears’ research on the Fruitlands experiment led to her involvement with the Harvard Shaker community. Alcott and his associates often visited the Shakers, with whom they felt a certain kinship in spite of their belief that the Shakers were too involved with commerce and enjoyed an unethical diet including meat and dairy products. Charles Lane lived in the Shaker community for a year after the Fruitlands experiment ended.

Sears’ research on the Fruitlands experiment led to her involvement with the Harvard Shaker community. Alcott and his associates often visited the Shakers, with whom they felt a certain kinship in spite of their belief that the Shakers were too involved with commerce and enjoyed an unethical diet including meat and dairy products. Charles Lane lived in the Shaker community for a year after the Fruitlands experiment ended.

When Sears first met the Shakers, they too faced dissolution, with just a handful of remaining members after a peak of some 200 in the 1850s. She became close to several of the eldresses, who asked her to write a book about the community; Gleanings from OId Shaker Journals was published in 1916. They also asked that she purchase and preserve the Shaker Office, a 1794 building located on the Church Family property on what is now Shaker Road. L. Kingston Savage moved the building to Sears’ property in 1916, where it was transformed by Sears into the Shaker Museum, the first of its kind in the United States. Two years later, the Harvard Shaker community closed, its members relocated to more viable communities and its buildings and land sold to Fiske Warren, a Boston industrialist and single-tax advocate. Some of the objects in the museum were later purchased by Sears from the Fiske Warren estate.

Native American Museum:

After Native American artifacts were uncovered during plowing on her property in 1928, Sears began collecting other artifacts both locally and from the western United States. She corresponded with experts in the emerging field of North American archeology, ethnography, and material culture, working closely with Warren King Moorehead of the Peabody Museum in Andover. She acquired most of her New England artifacts from Moorehead, and funded his archeological survey of the Nashua valley. Her collection also included many Sioux artifacts, most of which were purchased from Colonel A.B. Welch of Mandan, a National Guard officer from North Dakota and adopted member of the Yanktonai Sioux Nation.

The museum was created in two stages in 1929 and 1932. The front building was originally the North Still River schoolhouse while the rear building was an old barn. On either side of the front building are two sculptures created by Sears’ cousin Philip S. Sears. Pumunangwet (He Who Shoots the Stars, 1931) is a standing figure holding a large bow; Wo Peen, the Dreamer (1938), is a seated figure leaning on a bent knee and carrying a bow. Sears’ published The Great Powwow: The Story of the Nashaway Valley in King Philip’s War in 1934.

Art Museum:

The Art Museum, originally called the Picture Gallery, was the last to be created by Sears. The front gallery was constructed in 1941 to house Sears’ collection of primitive portraits from the early 19th century, then one of the largest of its kind in the United States. The rear gallery was added in 1947 to exhibit Sears’ collection of landscape paintings from the Hudson River School, a mid-19th century art movement influenced by Romanticism. Sears published Some American Primitives in 1941 and Highlights Among the Hudson River Artists in 1947.

Visit the Fruitlands Museum website